[Syria’s Apex Generation highlights post-uprising art as an introduction to the rich history of painting in Syria. Featuring the works of Abdul Karim Majdal Al-Beik, Nihad Al Turk, Othman Moussa, Mohannad Orabi, and Kais Salman, the exhibition and its accompanying publication explore a new school of painting in the midst of expansion despite the disintegration of the Damascus art scene, its original center. Informed by extensive traditions of expressionism, symbolism, and abstraction, this burgeoning group has forged ahead with the creative objectives of their predecessors, who advocated the social relevance of art.

The essay below is reproduced from the exhibition’s publication. Due to the essay`s length, its text has been divided between two posts. Part One appears below. Part Two can be found here. Syria’s Apex Generation is curated by the author and opens at Ayyam Gallery’s Al Quoz and DIFC locations in Dubai on 9 June and at Ayyam Gallery Beirut on 11 June.]

Since the start of the uprising in 2011, art has become integral to navigating the enormity of the Syrian conflict. For many artists reflecting on this time, the renewed status of visual culture—most profoundly felt in the abundance of digital media—has presented new challenges to the subjective domain of artistic production. Engaged in the fate of their country as dissidents, witnesses, and cultural interventionists, Syrian artists have openly questioned the role of art at every turn, publically discussing the ways in which form and representation can be used to communicate the consequent realities of war. Debates immediately surfaced and continue in the cultural pages of periodicals, on social media, in organized talks, and among the various circles now based throughout the Arab world.

Syrian artists have forever advocated the social relevance of art; a conception put forth in the early twentieth century by painters such as Tawfik Tarek (1875-1940), who established the first independent art studio open to the public. Syrian art reached several critical junctures in the decades that followed, and as the country faced transformative events its artists collectively recognized the shape-shifting capacity of visual culture. Through its progressive stages styles were set aside when breakthroughs were made and resonant traditions materialized. Before the present day realists, expressionists, and symbolists (satirists, subversives, philosophers, grievers, and optimists) there were the pioneers. Contemporary Syrian art reflects a creative upsurge that is nearly a century in the making.

In order to understand the era-defining period currently underway a historical reading of Syria’s predominant medium is necessary. Many of the intellectual debates of today resemble the dialectical processes that have guided Syrian art since easel painting was introduced towards the end of Ottoman Rule.

Modern Beginnings

Although the country’s formative period in art occurred between the start of the 1950s and the late 1960s, early innovators such as Michel Kurche (1900-73), Mahmoud Jalal (1911-75), Nazem al-Jaafari (b. 1918), and Naseer Chaura (1920-92) laid the foundation for mid-century modernists by defying the constraints of late Ottoman sensibilities and the cultural dictates of French colonialism, which produced a backlog of historical painting, Orientalist-informed genre scenes, and romantic portraits. Artists eventually outgrew these styles, opting instead for naturalistic renderings and the plein-air techniques and manipulation of color and light of the Impressionists that were the stepping-stones to modern art. Under the French Mandate a small group of artists were sent to study in Paris, including Michel Kurche; others like Mahmoud Jalal traveled to Rome; and just before independence Nasser Chaura and Nazem al-Jaafari trained in Cairo.[1]

While the influence of European artistic methods is evident in the work of this time perhaps a more significant fact is that as Syria transitioned into nationhood artists adopted a tonality in palette and overall emphasis on brushwork, thus communicating the interconnectedness of subjects with their surroundings. Whereas historical paintings and Orientalist compositions depict settings as static backdrops to staged scenes and classical portraiture focuses on rendering idealized physicality, this new approach sought intimate views: the lived realities of Syria. With understated expressiveness and the subdued hues of the country’s terrain, they painted cities, villages, and ancient sites, focusing on the rhythms of landscapes and the energy of street scenes. Figures and objects were rendered in portraits and still lifes with painterly treatments matching that of their environments, alluding to an intuitive sense of place felt across Syria’s diverse communities. This commitment to local subject matter continued into the modern period.

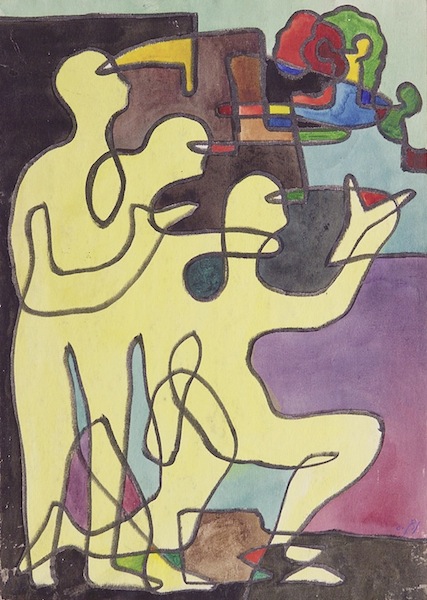

A 1951 painting by Adham Ismail (1923-63) is identified as the landmark work that confirmed the integration of modernist art modes.[2] Within the vertical composition of The Porter are stylistic details outlining the subsequent course of Syrian art. At the time of creating the historic painting, Ismail had been experimenting with the delineation of space found in Arabesques and the fluid line work of Arabic calligraphy. An untitled mixed media work on paper created in 1950 shows the preparatory exercises that would lead Ismail to develop his larger oil on canvas paintings. In The Porter the curvature of these line-based forms enclose small areas of matte color that make up the bodies of figures, unifying their different shapes. A large staircase diagonally divides the composition, and as the main protagonist ascends to an unknown location he crosses over the corpses (or perhaps spirits) of others. Although the laborer climbs with resolve, his muscular body folds under the weight of a parcel strapped to his back. This Sisyphean scene is contrasted with vertical blocks of color, which fade from dark to light, indicating the silhouette of a metropolis in the distance.

[Adham Ismail, Untitled (1951). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Adham Ismail, Untitled (1951). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

The Porter anticipates the major shift in aesthetics that would come just a few years later when artists began to earnestly depict the country’s disenfranchised population. The painting’s expressionist take on the measured build of Islamic art simultaneously confirmed that modern styles could be derived from the region’s artistic traditions, particularly through a reconsideration of precursors to the deconstruction of figuration and the reinterpretation of space found in modern art. Further explorations in form motivated several artists to abandon naturalism and the illusionist perspective of classical painting. Palettes were injected with bold color and abstraction entered compositions as a way of offsetting stylized subjects.

By the end of the decade a new generation had emerged. As these painters popularized modernist styles their impact was amplified with the expansion of the local art scene. The creation of a new wing devoted to Syrian art at the National Museum of Damascus in 1956 and the formation of the Faculty of Fine Arts in 1960, which remains the preeminent art school in the country, provided crucial institutional backing. Elsewhere, artists taught in secondary schools or opened studios offering instruction when academic training was unavailable. Art criticism began to shape cultural discourse while art associations gained in importance with the efforts of painters and sculptors who exhibited during the French Mandate and remained active after independence. One such artist was Nasser Chaura, who created the Society of Art Lovers with fellow Impressionist Michel Kurche in 1951 after opening the Damascus art hub Atelier Veronese with painter Mahmoud Hammad a decade before. Joining the Faculty of Fine Arts as a founding member of the institution’s teaching staff, Chaura influenced at least two generations of artists and worked alongside Nazem Al-Jaafari, Mahmoud Jalal, and Adham Ismail, among others, during a thirty-year tenure.

Social Realism, Expressionism, and Modernist Form

Although local painting adopted the usual path of modern art by the early 1960s, splitting between various schools of figuration and abstraction, an informal social realist phase just prior left a permanent mark on the Syrian imagination. Some historians have linked the motivation for this aesthetic thread to the cultural renaissance that orbited the Arab world’s mid-century political sphere.[3] Others have highlighted the biographical details that might have led certain artists to identify with commonplace or downtrodden subjects. While both theories are historically accurate, what is also revealing is that a number of the period’s artists studied in Egypt or Italy as significant social realist movements were underway; seminal among them were Adham Ismail, Fateh Moudarres (1922-99), Mahmoud Hammad (1923-98), Mamdouh Kashlan (b. 1929), and Louay Kayyali (1934-78). In Syria, brief trials with such imagery established a standard for engaging social concerns and addressing political issues or conflicts—a strand of realism that can be detected in decades of art regardless of style, technique, or time period. Bertolt Brecht’s criterion for realism in literature, which urged “making possible the concrete, and making possible abstraction from it,” can also be applied to artworks like The Porter, which revolutionized Syrian art. Since the modern period, numerous Syrian artists have reflected Brecht’s call for “discovering the causal complexes of society.”[4]

The modernists introduced what is identified as “effective form,” an approach to depicting reality that harnesses the plasticity of painting as a necessary source of ambiguity. Max Raphael first defined effective form in his 1941 essay Toward an Empirical Theory of Art, which argues that a work of art must not be created as an autonomous object based on a real-life model but should instead activate a sensory process of perception through the merger of form and content, objectivity and subjectivity. Revealing the material and temporal dimensions of context, effective form allows the viewer to “produce in himself the full import of the work, to renew it again and again.” Here it is worth noting that for Raphael context (or “the given situation”) contains the conflicted union of “a personal psychic experience and a sociohistorical condition,” which is further problematized by the artist.[5]

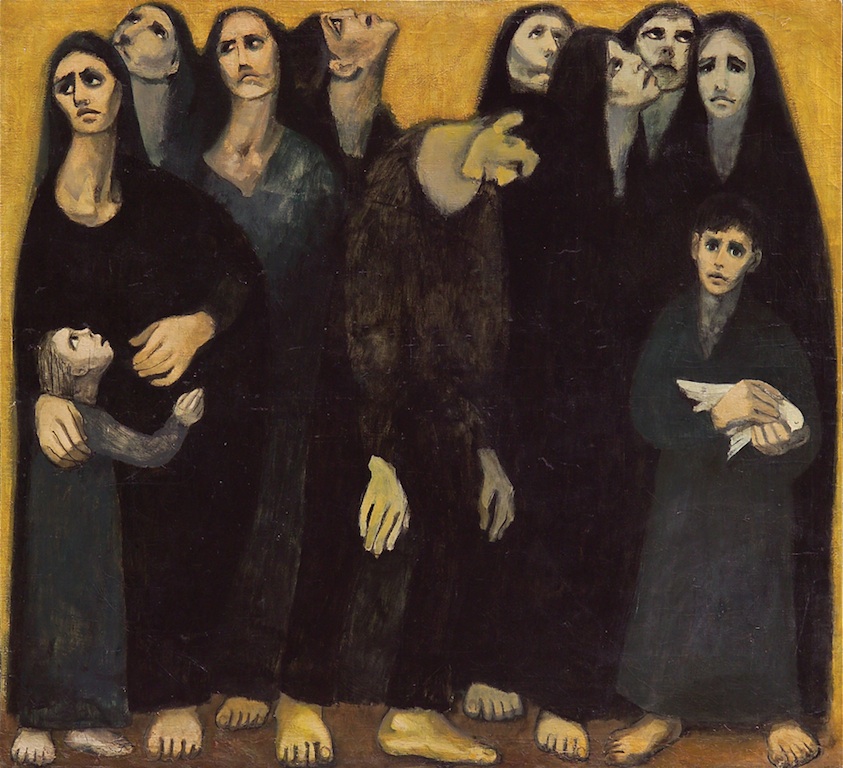

Painters Fateh Moudarres and Louay Kayyali typified this approach in their respective oeuvres despite contrasting aesthetics. After an interest in Surrealism and a momentary departure into abstraction while at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome from 1954 to 1960, Moudarres turned to ancient sculpture and bas-relief when modeling the protagonists of his paintings. With the hollow eyes of Sumerian figurines, the angular headdresses of Assyrian rulers, and the visible outlines of Byzantine icons, his figures embody the continuum of a culture shaped over millennia. He further emphasized this connection by affixing his subjects to their surroundings through tactile brushwork and unified color schemes inspired by the red-earth scenery of his ancestral village outside Aleppo. In the artist’s youth, the natural environs of the village embosomed him as a place of solace and discovery after his father was killed during a land dispute and his Kurdish mother was left to raise him in poverty.[6]

[Fateh Moudarres, Women at a Wedding (1963). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Fateh Moudarres, Women at a Wedding (1963). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

Asaad Arabi describes Moudarres’ works as stretching from the unconscious, particularly sites of memory, with alienated subjects ranging from the naïve and expressive to the secular and mythical.[7] Situated in compact, non-descript settings or against sweeping landscapes in which sky and earth collide without horizon line, the modernist’s statuesque figures are crowned the queens and kings of a congruous existence. Often appearing in units, the women and children, large families, and small communities of his paintings fluently move between the natural, spiritual, and mythological realms of Northern Syria. Writing on the artist shortly after his death in 1999, Abdulrahman Munif observed that Moudarres’ paintings vary between “martyrdom, crucifixion, and departure.”[8] The artist’s experience of displacement, initially from the countryside to Aleppo and later to Damascus amid the agricultural crisis of the 1960s, heightened his awareness of class struggle and the underside of a society encumbered by the machinations of power. This emerged as a central theme in his many years of painting, most acutely during periods of militarized conflict in the Arab world. According to Munif, the summation of Moudarres’ work constituted a rebellion.

[Fateh Moudarres, Maaloua (1974). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Fateh Moudarres, Maaloua (1974). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

In Moudarres’ canvases vigorous strokes and densely painted areas of color are rendered in a manner similar to the automatic brushwork of Abstract Expressionism and its European parallel Art Informel. The post-war movements sought to activate subconscious creation by borrowing from the lessons of Surrealism. Louay Kayyali stood as Moudarres’ formal polar opposite with a comparatively subdued execution of his subjects, whose soft-edged bodies are delicately shaped with thin black lines. Although an accomplished draftsman prior to arriving in Rome, Kayyali’s style was refined at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. The younger artist alternated between lightly shaded areas of color and slightly textured surfaces, making the focus of his compositions their rounded forms. Kayyali’s method of envisioning his subjects as sequences of lines and curves given volume through temperate tonal variations stems from the influence of Early Italian Renaissance painting, the direct evidence of which is found in his recurrent adaptation of Madonna imagery. He first experimented with this approach to figuration—which brings to mind the frescoes of Giotto—while in Italy in the late 1950s. Visiting Syria as he neared the end of his artistic training, he began to foresee how such stylization could be used to engender art as a form of social discourse.

Like Moudarres, Kayyali viewed Syria as “two contradictory societies” divided between the concentration of wealth in the cities and the concurrent marginalization of rural villages.[9] Indicating the global popularity of Social Realism at the time, specifically among artists working in formerly colonized nations, Kayyali joined the broader movement of modernist painting that placed disenfranchised subjects as contemporaneous icons of political struggle. Although his figures are dignified, the Syrian painter avoided romanticizing their lives; in order to project “the refusal of the given social condition,” as Kayyali advocated, art must “look objectively.”[10] The fatigue and alienation of his solitary protagonists often register the experiences of impoverished workers and their neglected communities, recalling the motifs of Italian Neorealism. The artist frequently utilized the physical limitations of the picture plane to establish the mood of his portraits; as his models are rendered with imposing stature, the borders of the composition simultaneously frame them in isolation against vacant backgrounds. In 1959 Kayyali painted a self-portrait with an austere conceptualization of space as an affecting detail. Depicted in the clothes of a worker, his slender form appears bent, depleted, and trapped by the narrow dimensions of its Masonite board. Emulating the aged quality of frescoes, Kayyali applied several layers of medium over roughly prepared gesso then reworked the surface of the painting to expose its lower layers.

[Louay Kayyali, Untitled (1959). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Louay Kayyali, Untitled (1959). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

Kayyali’s investigation of the allegorical potential of historical forms is also visible in the prophetic painting Then What? (1965). In the large-scale work huddled women and children encircle a lone male figure. Facing the viewer and paused in uncertainty, they appear in mid journey. The painting’s central protagonist is shown with convex posture; the contortion of his body signaling exhaustion, defeat, or despair, as he is loosely rendered and defined by slack lines. A female figure behind him gazes towards the sky, stretching in fear at the sight of something overhead. This focal point pairing resembles Masaccio’s shell-shocked Adam and Eve in the fresco panel The Expulsion from Paradise (1427).[11] Kayyali extends the drama of this familiar scene, creating an explicit association with the biblical narrative.

[Louay Kayyali, Then What? (1965). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Louay Kayyali, Then What? (1965). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

Undoubtedly representing a displaced people captured in a moment of escape, Then What? evokes the ongoing plight of Palestinian refugees, a subject previously addressed by Mahmoud Hammad and Adham Ismail in 1958 and 1960, respectively. When painting The Refugees Ismail substituted atmospheric washes, naturalist portraiture, and deliberate strokes for his signature expressionist lines and sectional color fields. Ismail’s style adjustments reveal the type of formal demands that were considered when artists approximated the zones of catastrophe.

For the Sake of the Cause

When Kayyali addressed such themes he released the bodies of his figures from the solidity of careful outlines that canonized pensive mothers, fishermen, street vendors, and shoeshine boys. Without losing the apparent monumentality he applied throughout, he exited the stillness of daily life to enter the chaos of war. In 1967 he finalized a series of charcoal and mixed media works titled For the Sake of the Cause, which were exhibited at the Arab Cultural Center in Damascus and later toured the country. Shown in dark fatalistic scenes, men and women are caught in cataclysmic violence, or else visibly tormented by the fear of an anticipated fate. According to biographical accounts, the artist began the series in 1966 as a general exploration of the forlorn state of modern man.[12] Critics and artists disparaged the work, deeming it excessively pessimistic. Kayyali was deeply affected by this unforeseen response and sunk into depression, destroying most of the series. Thereafter, he ceased to produce art for several years. When he returned to painting in the early 1970s, he focused on the emotive impact of color and enhanced the robustness of his figures.

The political debacle of the Six Day War tested the parameters of visual culture and changed the course of Syrian art. Notwithstanding the overstated reaction to the social realist’s emphatically political works, the setback of 1967 led artists to resuscitate the utility of art through experimentation. Abstracted space, viscous brushwork, assertive markings, and densely textured surfaces are but a few of the formal attributes characterizing this new direction.

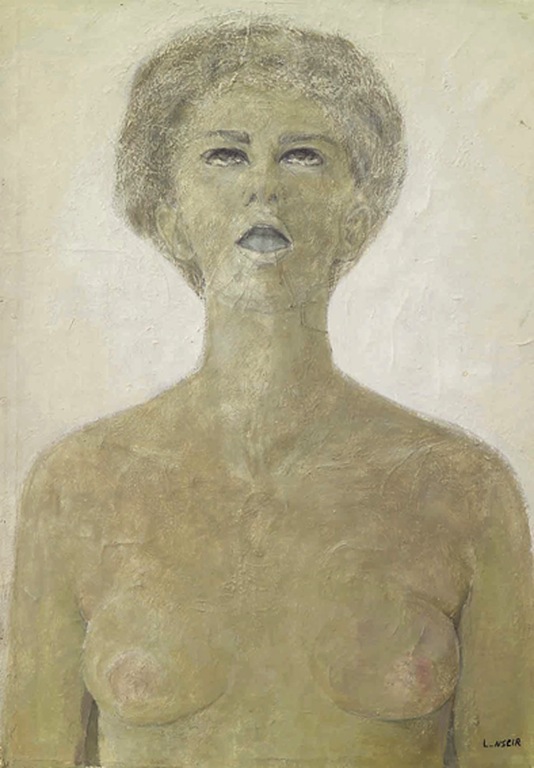

Like Kayyali, Leila Nseir (b. 1941) prefigured the turn in Syrian art that would come as regional political tensions boiled over. A 1965 self-portrait shows the artist disrobed while gasping for air, or perhaps screaming, into nothingness, as her nude torso suggests a moment of vulnerability. Nseir’s exposed body is executed in a muted palette with reserved line work that points to the influence of ancient Egyptian art.[13] The visual impact of such simplified forms causes the viewer to rest their gaze on the sculptural figure that stands before them. Gradations in color guide the eye upward, beginning at Nseir’s softened shoulders before arriving to her troubled expression. The transgressive nature of the self-portrait is manifold. Its withdrawn appearance, which is achieved with a lack of warm hues, implies the image of a departing body or a woman attempting to break free from a constrictive environment. Moreover, by painting herself with such disconcerting intensity, Nseir disrupts the traditional portrayal of the female nude, ridding it of sensual or maternal triggers.

[Leila Nseir, Untitled (1965). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Leila Nseir, Untitled (1965). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

When the conflagration of 1967 erupted, those at the start of their careers such as Elias Zayat (b. 1935), Nazir Nabaa (b. 1938), Ghassan Sebai (b. 1939), Leila Nseir, Asaad Arabi (b. 1941), and Asma Fayoumi (b. 1943) were positioned to lead the transition of local painting from modernist modes to contemporary methodologies. Yet for some, the unanticipated outcome of the war and the ongoing deterioration of the Syrian political situation complicated this process, requiring a new form of objectivity. Asma Fayoumi, who entered the Syrian art scene with abstract paintings guided by her time at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Damascus, cites the social exigencies of an era seized by war as the determining factor for her sudden switch to figuration and the expressionist style that consequently distinguished her oeuvre.[14] Others of this cusp generation proceeded with recognizable styles informed by Syrian cultural signifiers. By placing recurring figures within the desolation of ravaged settings, however, the symbolic worlds of these modern topographers were transformed into the psychological landscapes of war.

[Asma Fayoumi, Qana (1998). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Asma Fayoumi, Qana (1998). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

In Nazir Nabaa’s Napalm (1967) a distressed nude woman screams as the thew of her body is stretched to its outermost limits. Shrouded in an infernal light that swallows the earth around her, she appears to belong to the artist’s mythology-inspired series of goddesses. Although indistinguishable if she is captured in the moment before or after a chemical attack, the fraught contortion of her face and body are frozen in an instance of suspended time. Nabaa later reproduced his martyred heroine in a similar pose in a painting titled Bahr el Baker School (1970), which depicts the Israeli bombing of a site in Egypt that killed dozens of children. Sheltering a pair of boys who crouch in fear, she thrusts her body upward as a building collapses and wreckage rains down. When depicting the havoc of the scene, Nabaa employed a cubo-futurist configuration of space that captures the moments before their fatal end, the terror of which is magnified through geometric implosion.

Expressionist techniques were utilized by painters who searched for reflective ways to negotiate the fallout of war and the political crises that ensued. Fragmented into rectangular squares of differing shapes, Asaad Arabi’s Migration to Quneitra (1973) depicts the path of anonymous figures as they move across the foreground of an abstracted scene. Executed in earth tones accentuated by warm hues of reds and gold, their thickly painted bodies appear to melt into their environmental passageway. The title of the composition references the short-lived recapture of a town in the occupied Golan Heights during the October War. Displaying the artist’s gradual move towards nonobjective art that would culminate in geometric abstraction several years later, the painting relies on the construction of space in order to invert it, which Arabi views as a pretext to enter the “intuitive internality” of things. Although faceless, the roughly rendered migrants seem to walk with a solemn pace of apprehension.

Evident in the art of the time is a cathartic form of bearing witness, allowing viewers to confront what is unnamable but nevertheless experiential. To achieve such visual profundity artists modified the aesthetic bases of modern Syrian painting, which by then were steeped in symbolism, allegory, and stylization. A modernist perception of form that communicates movement across time is extended into an existentialist double portrait in Ghassan Sebai’s Fear (1977). Engulfed by a nameless force, the protagonists of Sebai’s composition are painted with cubist renditions of materiality, allowing the shapes of their bodies to appear in motion as they draw close in search of relief. Overcome by fright, the stout figures are broken into abstracted spaces of color.

[Ghassan Sebai, Fear (1977). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Ghassan Sebai, Fear (1977). Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

As further turmoil marked the decades that followed, artists assumed the task of routing psychic exits as they passed through an abject state of isolation.

Continue reading (Part Two).

Footnotes

1. Contemporary Art in Syria 1898-1998, ed. Mona Atassi (Damascus: Gallery Atassi, 1998).

2. Tarek Al-Shareef, "Contemporary Art in Syria," trans. Dr. H. Dajani, Contemporary Art in Syria 1898-1998, ed. Mona Atassi (Damascus: Gallery Atassi, 1998).

3. Zena Takieddine, "Arab Art in a Changing World," Contemporary Practices, Vol. 8 (Fall 2010).

4. Bertolt Brecht, "On the Formalistic Character of the Theory of Realism," trans. Stuart Hood, Aesthetics and Politics, ed. Ronald Taylor (New York, London: Verso, 1980).

5. Max Raphael, The Demands of Art, trans. Norbert Guterman (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, LTD, 1968).

6. See Fateh Moudarres’ essay, "Dans Les Labyrinthes De La Mémoire," Moudarres (Damascus: Galerie Atassi, 1995).

7. Asaad Arabi, ‘Matière De L’Oubli Et De La Mémoire,’ Moudarres (Damascus: Galerie Atassi,1995).

8. Abdulrahman Munif, "Fateh Moudarres, Syrian Artist Who Fought for Justice with Brush, Pen," trans. Elie Chalala, Al Jadid, Vol. 5 no. 29 (Fall 1999).

9. Louay Kayyali, "Art’s Linkage to the Reality of the People: Or Art’s Ties to the Reality of the Revolution,"trans. Hiba Morcos, ArteEast Virtual Gallery, http://www.arteeast.org/2012/03/04/arts-linkage-to-the-reality-of-the-people-or-arts-ties-to-the-reality-of-the-revolution/, as of 6 May, 2014.

10. Ibid.

11. For an in-depth reading of this particular work see the author’s "Of Poets and Men: Allegory, Reality and Abstraction as Intersections of Art and Politics," The Samawi Collection: Curated Selections of Arab Art, Volume I (Dubai: Ayyam Gallery, 2011).

12. For further information see the ‘biography’ page of www.louay-kayali.com, which includes a timeline of the artist’s life by Fadel El Sibai.

13. Rashed Issa, "Experimenting and Living Art Essential," Leila Nseir (Damascus: Ayyam Gallery, 2008).

14. Maymanah Farhat, "Destruction and Renewal in the Paintings of Asma Fayoumi," Asma Fayoumi (Damascus: Ayyam Gallery, 2010).